This NSFW post is written for the Movies That Haven’t Aged Well Blogathon, hosted by MovieMovieBlogBlog. Here is where you can find the announcement and entries to date.

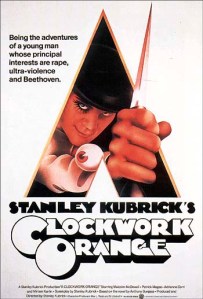

With some trepidation, I’ve chosen to write about A Clockwork Orange.

Because this is a noir blog, let me say that I’m reading Kubrick’s film as neo-[SF-]noir, for its cynicism, its violence, its focus on the underside of middle-class life, its sexism, and its mis-en-scene.

I also want to provide the backstory that I adored this film as a teen. I loved the rebelliousness (I even kicked out a window in a local elementary school…without any clue as to why I needed to do it). I identified with the combination of classy and trash tastes (I loved Shakespeare and Aerosmith in equal measure). And I had the hots for Malcolm McDowell. I even dressed as Alex for Halloween my sophomore year, having been introduced to the film in my Advanced Psych class, where we watched scenes to learn about the difference between classical and behavioral conditioning. (I moved on by senior year to Rocky Horror Picture Show, I’m proud to say.) Never mind that I had to look away during the Singing in the Rain rape scene; I loved that Alex fought the system and won. Down with the System!

But let’s get to the focus of the blogathon…

Top Three Ways in Which A Clockwork Orange Has Not Aged Well

3. The Decor

This is an easy attack. Every film that enters the “futuristic” realm is going to age, and badly at that. The future has to be based on the present because it is the present-day of the film production that guides how the future will be seen. Even more than aliens can’t look truly “alien” because they come from the human experience and imagination, the urban/suburban landscape of A Clockwork Orange says more about the early 70s than it can ever say about the fictional future it envisions.

Top on the list of elements that haven’t aged well to my eyes is the decor:

2. The Sexism

The sexism of A Clockwork Orange has been critiqued from its first day of release, its director even being called misogynistic for his cinematographic choices. Certainly, there is no question that Alex, his droogs, and their entire generation are exemplars of sexism. They practice and celebrate what we now call “rape culture,” with Alex coercing the under-aged when he isn’t raping adult women.

This means that the film had no possibility of aging well in its portrayal of women. And the male gaze dominates the filming of the sex-rape-torture scenes:

There is no question that the film can be discussed from a feminist perspective. Surely the film isn’t pro-torture and rape of women, we might argue; it’s a critique of objectification and misogyny. It’s satire.

The problem is that Alex is our anti-hero and Kubrick gives us no preferable alternative perspective. Again, we can say this is one of the things that’s wrong with the world — and the condemnation of women as leading to men’s ruin is definitely a part of the film noir tradition. But at least the femme fatale has some power, some voice. All most of the women of this film do is show their bodies, get attacked, and either flee or die. The exceptions (apart from Alex’s weepy embarrassing mum) include Dr. Branom and Alex’s psychiatrist at the end of the film. The former is an emotionless prune who keeps the Beethoven playing as Alex undergoes “therapy,” while the latter is a motherly vehicle through which Alex gets back to his former misogynistic self.

1. The Ending

That our anti-hero Alex ends the film having bested the system with even a possible future career in politics ahead of him definitely pleased me as a teen. In my world of parental rules and teachers’ demands, Alex was my favorite rebel.

As an adult looking back, however, the film doesn’t please me. It’s not that I don’t still resist social strictures and fight the power. It’s that the film doesn’t let him mature, another critique of the film when it first emerged on the big screen. Kubrick cut off the final chapter of Anthony Burgess’s novel, the one where Alex grows up and becomes the typical middle-class asshole he ranted and did violence against as a youth. Thus, the novel is at least in part about the callous, ruthless, blind nature of youth. And the film isn’t.

So maybe, in the end, my central point is that I’ve aged well but A Clockwork Orange never got the chance.

That’s all from this humble narrator, droogies. Hope you’ve viddied well and found this post horrorshow.

July 26, 2015 at 12:50 AM

I agree with you in every instance! Like you, I was impressed with the first movie upon first viewing (although I didn’t see until it was shown in a college film class), but I think it has aged terribly and is quite as misogynist as you point it out to be. Well done, and thanks for contributing to my blogathon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

July 26, 2015 at 12:53 AM

Happy to contribute, though it wasn’t easy to choose a film. So much of noir is dated in the usual ways but the genre ages well, even when its sexist, racist, and badly written!

LikeLiked by 1 person

July 26, 2015 at 1:26 AM

I confess I didn’t watch it at the time of its release, despite being deeply involved in the sf scene back then — it just seemed to me to be a complete exploitationer. I guess that at some time I’ll watch it, but somehow there’s never seemed any pressing urgency to do so.

LikeLiked by 1 person

November 12, 2015 at 2:00 AM

Maybe the problem is less how the movie has aged and more that you originally came at it from the angle of viewing Alex as a hero?

LikeLiked by 1 person

November 12, 2015 at 2:29 AM

Could be, at least for my perspective on him. Especially before reading the last chapter of the novel.

LikeLike

February 25, 2016 at 12:05 AM

Pretty much on point there, very good analysis…however I still love the decor of the Moloko bar

LikeLiked by 1 person

February 28, 2016 at 12:40 PM

Unfortunately, I saw this film for the first time at a party with new coworkers in the 90s. Everyone had to leave right after, and I was completely traumatized, and didn’t know my new coworkers well enough yet to say so or inquire what exactly I’d witnessed. I don’t think I’ll ever get past that first impression enough to admire what’s good about this film!

LikeLiked by 1 person

February 28, 2016 at 4:35 PM

I completely understand. To me as a teen, it was rebellion and fight the power and I just kind of turned away from the the rape scenes. Now it’s not only cheesy but disturbing. The rape in particular did not need to be shown graphically: it traumatizes the caring and titillates the misogynist.

LikeLike

October 29, 2016 at 8:07 PM

I saw this when first released and had a peripheral feeling for what was going on. I was in my twenties and “kinda” got it (I was further on my way to “alternative thinking”). Didn’t pick it up ’til I moved here to Charlottesville 16 years ago (I’m currently 62). It’s one of my go-to movies these days……..I simply really like this movie. It’s heightened my appreciation for Kubrick…..I want the 10 movie collection (“Dr. Strangelove” was a pre-teen experience that has also lingered forever ).

MOA–4:02 PM–ex-wife’s place–Charlottesville, Va. 22901

LikeLike

November 25, 2016 at 5:16 PM

I couldn’t finish it – but not because of the content, which elicited more laughter than shock from me – but because of the dreadful sets, music (outside the classical pieces, of course) and general approach to filmmaking. Within the first five minutes I remarked out loud “God I hate the 70s!” .. with very few exceptions, the vast majority of late 60s and early 70s movies are seriously unwatchable.

At any rate, having said all that – there was one scene that I completely loved.. the slow motion walk along the waterway in which McDowell assaults his fellow droogs was masterful.

As for the rape and misogyny bit .. I’m not really sure how you expect a movie to attempt a realistic look at a shocking rape without including what you would call “rape culture” and “the male gaze” .. that’s like calling Schindler’s List anti-semitic because it depicts the slaughter of Jews.

At any rate, thanks for the write up – I enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 2 people